How to Change A Habit

Habits are the choices all of us deliberately make at some point, and then we just stop thinking about but continue doing, sometimes everyday. Habits are decisions that have become automatic behavior. They emerge because the brain is constantly looking for ways to save effort.

Habits are the choices all of us deliberately make at some point, and then we just stop thinking about but continue doing, sometimes everyday. Habits are decisions that have become automatic behavior. They emerge because the brain is constantly looking for ways to save effort.

So far we’ve learned that the average time to develop a habit is 66 days. We’ve also learned that missing a day in the habit-formation process doesn’t mean you have to completely start over—thank God!

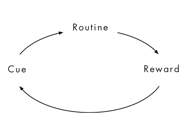

In our last article we also learned that new habits are formed by what researchers at MIT describe as the habit loop. The habit loop consists of three parts: a Cue, a Routine and a Reward. A Cue is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. The Routine is the activity you perform almost automatically after you encounter a Cue. The Reward is what helps your brain figure out if a particular Routine is worth remembering for the future.

Like it or not, we all have Cues we associate with certain rewards that create almost insatiable cravings within us. For many of us, the chime of incoming email is a Cue that initiates a powerful craving to check our inbox to see if we’ll be rewarded with some life-altering news. For others, the Cue of putting on running shoes creates a craving for the reward of a runner’s high, which compels them to get out the door and start running. Once our brain associates a Cue with a Reward, an un-erasable habit begins to encode itself within our basal ganglia.

Neuroscientists have learned that once our brain encodes a habit, the habit never really disappears. It’s always there looking for that certain Cue to initiate the habit sequence. That wouldn’t be a problem if all our habits were good for us. Unfortunately, our brain doesn’t distinguish between good habits and bad ones. It will off-load any repeated activity to the basal ganglia, even if it’s something harmful like smoking cigarettes.

So we all have habits we would like to change—things we do on a regular basis that harm our health or the well being of our family. Maybe it’s binge eating, wasting time at the office or overspending. We’ve all failed at trying to change bad habits in the past. So with new research available on habits, surely there is a simple method for changing an undesirable habit.

The problem? There isn’t one formula for changing a bad habit. There are thousands. Individuals and habits are all different, so the aspects of changing the patterns in our lives differ from person to person and behavior to behavior. Giving up smoking is different from giving up sodas, which is different from changing how you react to your kids, which is different from how much time you spend playing video games. Also, everyone’s habits are driven by different cravings. But somehow, every day, people find ways to change undesirable habits. Change doesn’t always come quickly and it usually isn’t easy, but with time and effort almost any habit can be reshaped.

Charles Duhigg, in the Appendix of his book Power of the Habit, gives a four-step framework for changing undesirable habits.

THE FRAMEWORK:

- Identify the routine

- Experiment with the rewards

- Isolate the cue

- Have a plan

Step One: Identify The Routine

As mentioned above, there is a simple neurological loop at the core of every habit. The loop consists of three parts: a Cue, a Routine, and a Reward.

To understand how to change a habit, you must first identify the components of its habit loop. Once you have identified the loop, you can look for ways to replace old vices with new routines.

Let’s say you are trying to change your habit of going to your favorite coffee shop to get a premium (high calorie) latte every afternoon. You know the habit is bad for your because you’ve gained a few pounds. You tried to force yourself to quit, but every afternoon you find yourself driving to the coffee shop to purchase a cup of sugary caffeinated delight.

In this habit loop, getting a premium coffee every afternoon is the Routine you want to change. Now that you know the Routine, you have to ask yourself some less obvious questions: What’s the Cue for this routine? Is it lack of energy? Boredom? Low blood sugar? Do you need a break before starting your next task?

In this habit loop, getting a premium coffee every afternoon is the Routine you want to change. Now that you know the Routine, you have to ask yourself some less obvious questions: What’s the Cue for this routine? Is it lack of energy? Boredom? Low blood sugar? Do you need a break before starting your next task?

You’ll also need to ask yourself what the reward really is? The coffee itself? The change of scenery? The temporary distraction? Socializing with colleagues? Or the burst of energy that comes from the sugar?

To figure this out, Duhigg suggests you do some experimentation.

Step Two: Experiment With The Rewards

Rewards are powerful because they satisfy cravings. To figure out which cravings are driving the habit you wish to change, it’s useful to experiment with different rewards. This could take days or weeks. During this experimentation period, don’t put any pressure on yourself to change the habit—think of yourself as a scientist collecting data.

On the first day of your experiment, when you feel the urge to go to the coffee shop, adjust your routine so it delivers a different reward. For instance, instead of going to the coffee shop to get a premium latte, eat an apple. The next day go for a 15-minute walk, and then go back to work. The next day, take a break and talk to some colleagues for 15 minutes.

Test different hypothesis to determine which craving is driving your routine. Are you craving the coffee itself or a break from work? If it’s the coffee, is it because you’re hungry or you just need some energy? (In which case the apple or the 15-minute walk should work just as well.) Or are you going to the coffee shop to socialize? (If so, socializing with colleagues should satisfy that urge.)

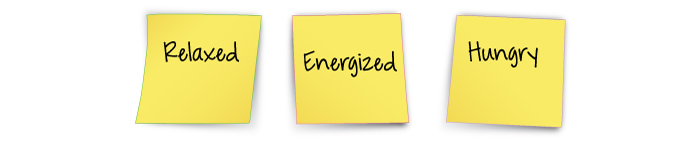

As you test four or five different rewards, write down on a piece of paper the first three emotions, random thoughts or reflections that come to mind when you get back to work.

Then set an alarm for 15 minutes. When it goes off, ask yourself: Do you still feel the urge for that latte?

It’s important to write down three things even if they are meaningless words. Doing so will force a momentary awareness of what you are thinking or feeling. Studies show that writing down a few words helps in later recalling what you were thinking at the moment.

The fifteen-minute alarm will help you determine what you’re craving. If fifteen minutes after eating an apple, you’re still craving a sugary latte, then your habit isn’t motivated by a sugar craving.

On the other hand, if fifteen minutes after going for a short walk your craving is gone, you’ve identified the reward—temporary distraction and a boost in energy.

Experimenting with different rewards will allow you to isolate what you’re actually craving, which will allow you to redesign the habit.

Step Three: Isolate The Cue

Identifing what Cue triggers a particular habit is hard because we have so much information bombarding us everyday as our behaviors unfold. Ask yourself, do you eat breakfast everyday at a certain time because you are hungry? Or because the clock says 6:30? Or because your kids have started eating? Or because you’re dressed and that’s when the breakfast habit kicks in?

Luckily, scientists have figured out that all habitual cues fit into one of five categories:

Location

Time

Emotional State

Other People

Immediately preceding an action

So if you’re trying to understand why you have the urge to get a sugary latte every afternoon, write down the answer to the following five questions every time the urge hits:

Where are you? (at work, driving, at home)

What time is it? (2:00 p.m.)

What’s your emotional state? (bored, tired, happy)

Who else is around? (nobody, a friend, your spouse)

What action preceded the urge? (wrote an email, reading book, finished a call)

Write down the answers to these questions until you can clearly see which Cue is triggering your habit.

Step Four: Have A Plan

Once you’ve figured out your habit loop—you’ve identified the Reward driving your behavior, the Cue triggering it, and the Routine itself—you can begin to change the behavior.

As we discussed earlier, a habit is a formula your brain automatically follows: When I see a CUE, I will do ROUTINE in order to get a REWARD. To change the formula, you need to begin making choices again. The easiest way to do this, according to study after study is to HAVE A PLAN!

Let’s use the latte example to help us understand how to develop a good plan. Let’s say that by using the first three steps of this framework, you have learned that everyday at 2 p.m. your brain received a Cue to get a sugary latte, the Routine is to drive three blocks to the coffee shop and purchase a premium coffee drink, you also learned that it wasn’t really the latte you craved—you learned that it was a temporary distraction and an energy boost.

A plan to change this habit might look like this:

-At 2 p.m. every day, I will go for a fifteen-minute walk.

-To make sure I do this, I will set an alarm on my clock.

Realize that when you first to try change a habit you will have failures. If you ignore your alarm today, try again tomorrow. Work to get more and more days of establishing your new habit each day. Changing some habits will be harder than others, but this framework is a place to start. Remember the average time for starting a habit is 66 days.

Some habits will require repeated experiments and failures, but once you understand how a habit operates, you gain power over it. One small shift in perception can touch off a series of changes that can radiate throughout every part of a your life.

Focusing on changing just one habit can teach you how to reprogram other routines in your life, as well.

There’s nothing you can’t do if you get the habits right.

Stay Strong

Bo Railey