Strength Training: Why It’s Essential for Strong Bones

The term osteoporosis means “porous bones.” It affects 20% of women and 5% of men over age 50. One out of two women and one out of eight men will experience an osteoporosis-related fracture in their lifetime.

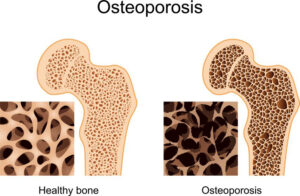

Osteoporosis is a condition where bones deteriorate to the point that they are brittle and porous (having minute spaces or holes). People with osteoporosis often experience broken bones simply by coughing or bumping into something. The hip and the spine are the most likely sites for an osteoporotic fracture. In older women, the spine can break and collapse to the point that they get shorter and can’t stand up straight.

The most serious consequence of osteoporosis is a broken bone in the hip. Many people who break their hip can’t live on their own and are more likely to die sooner. With osteoporosis, the hip can break spontaneously, resulting in a fall—the opposite of what should happen.

Women experience a greater risk of osteoporosis after menopause because of the significant decrease in estrogen. Estrogen maintains bone mass by decreasing the lifespan of osteoclasts (bone crushing cells) and increasing the number of osteoblasts (bone building cells). Scientists have struggled to understand how estrogen makes this happen, but a recent study revealed estrogen is responsible for expression of a protein in bone cells that promotes their survival. Estrogen also helps the intestines absorb calcium and reduces urinary calcium excretion.

Most people don’t know they have osteoporosis until they break a bone. That’s why screening is important. Doctors recommend screening for osteoporosis for women over 65 or postmenopausal women over 50 whose parent has broken a hip.

Doctors typically screen for osteoporosis with a DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) scan, which measures bone mineral density at the spine, hip, or total body. A DXA scan produces a T-score, which compares your bone mineral density to that of a normal healthy young adult.

Your T-score represents the number of units (standard deviations) your bone density is above or below the average. A T-score of -1 to -2.5 indicates osteopenia, which means bone density is below normal and may lead to osteoporosis. A T-score below -2.5 indicates osteoporosis.

Treatment for osteoporosis typically involves a class of drugs called bisphosphonates. Fosamax, taken daily, weekly, or monthly, seems to be the most popular. Bisphosphonates strengthen bones by slowing the rate at which the body removes calcium. Bisphosphonates have a considerable list of side effects such as gastrointestinal problems, trouble swallowing, inflammation of the esophagus, and ulcers.

If you have osteoporosis and your doctor puts you on prescription medication, stick to your doctor’s plan. But do everything you can to improve your bone health. It’s not an easy task, but we’ve had several of our clients improve their bone mineral density to a level that allowed them to stop taking bisphosphonates.

We usually think of bone as lifeless tissue, but it’s not. Bones are metabolically active organs that undergo continuous remodeling throughout life. Bone remodeling involves the resorption of old or damaged bone, followed by the deposition of new bone material.

In the 19th century, German anatomist and surgeon Julius Wolff developed a theory of bone remodeling known as Wolff’s law. His law states that bone in a healthy animal will adapt to the loads under which it is placed. If loading on a particular bone increases, the bone will remodel itself over time to become stronger to resist that sort of loading. Stress causes bones to become denser and stronger. The inverse is true as well: if loading on a bone decreases, the bone will become less dense and weaker.

Wolff’s law explains why strength training is so important to bone health. When we think of lifting weights, we usually only think of building stronger muscles. But strength training is just as beneficial for your bones. Wolff’s law explains that your bones, like most biological tissues, are subject to a “use it or lose it” principle. Many older adults simply don’t subject their bones to enough stress for them to be healthy.

The uniquely slow method of strength training we use at Exercise Inc was developed for older women who needed to strengthen their bones. Lifting weights can be dangerous if it isn’t done properly. The biggest mistake most people make when they lift weights is going too fast. Faster speeds subject the joints to more kinetic energy, which is what causes injury. At slower rates of speed, anyone can lift heavy weights safely. And that’s exactly what happened in the osteoporosis study where our slow method of lifting was developed. The women had a 30% greater increase in strength than had ever been seen in any other strength training studies.

Several studies have shown strength training to be safe for people with osteoporosis. A recent study had 101 osteoporotic women aged 65 and older lift heavy weights (85% of their 1 rep max) for 8 months. There was only one adverse event. One woman reported back spasms. The study also showed a significant reduction in curvature of the spine—they were able to stand up straighter.

A study published in 2020 reviewed the five leading studies on strength training’s effect on osteoporosis. Four of the five studies showed a significant increase in lumbar spine bone mineral density after strength training interventions. The fifth study confirmed maintaining bone mineral density due to strength training exercises. Three of the reviewed studies showed a significant increase in femoral neck density.

We view strength training as an essential component of bone health. The training needs to be intense and safe. The weights need to be heavy. If bones are going to get stronger, they need to be exposed to mechanical loads exceeding those experienced during daily living activities. The kind of strength training we do at Exercise Inc is the kind of training required for strong, healthy bones.

Stay Strong,

Bo Railey