Can Exercise Prevent Suicide?

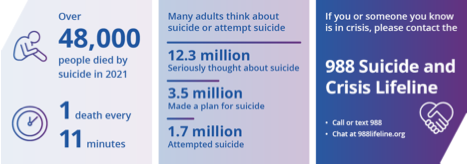

You’ve probably heard that September is National Suicide Prevention month. The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline has gotten a lot of press lately, and for good reason. The CDC considers suicide a leading cause of death, and suicide rates in the U.S. increased 36% from 2000 to 2021.

The numbers are staggering: 48,000 died by suicide in 2021, about 1 death every 11 minutes. Also in 2021, 12.3 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.5 million planned to attempt suicide, and 1.7 million attempted suicide. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people aged 10 to 14 and 20 to 34.

Also, suicide rates by active-duty military are currently at an all-time high since record keeping began after 9/11 and have been increasing over the past five years at an alarming rate. The first quarter of 2023 was the third worst for Army suicide rates since 2017. In 2021, research found that 30,177 active-duty personnel and veterans who served in the military after 9/11 have died by suicide—compared to the 7,057 service members killed in combat in those same 20 years. Military suicide rates are four times higher than deaths that occurred during military operations.

Most people who commit suicide have a mental disorder, most commonly a depressive disorder or a substance use disorder. It’s often said that depression is the result of a chemical imbalance in the brain, but it’s more complex than that. There are many possible causes of depression, including faulty mood regulation by the brain, genetic vulnerability, and stressful life events. Typically, several of the sources interact to bring on depression.

Medication and cognitive behavioral therapy are the most common treatments for depression. But what about exercise? We know it makes us feel better, but does it really work as an antidepressant, and is it potent enough to prevent suicide?

Mental and physical health are intimately connected. People with chronic physical conditions are more likely to develop mental illness, and people with mental illness possess a greater likelihood to suffer from a variety of other medical conditions. Researchers have associated mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, which is likely attributable to adverse impacts on sleep, autonomic and endocrine dysregulation, and lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet and physical inactivity.

Exercise has the unique ability to simultaneously improve the physical and mental health of an individual, even at levels below public health recommendations. The U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines have recently acknowledged that physical activity improves cognitive function and decreases anxiety and depression. Numerous studies have shown the positive impact of exercise on depressive symptoms to the point of remission. Let’s look at what some of those studies have to say.

A meta-analysis published in 2023 looked at 17 randomized control trials involving 1,021 participants regarding suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The study found that exercise did not have an effect on suicidal thoughts. But exercise did significantly reduce suicide attempts. This study is a little discouraging, but probably realistic—exercise might not necessarily change your thoughts, but it can change your actions.

A study conducted in 2015 found exercise just as beneficial as cognitive behavioral therapy when dealing with depression. The study, a 12-week intervention, included 945 adults experiencing mild to moderate depression. Some of the adults received cognitive therapy for 12 weeks, the other group participated in supervised exercise three times a week. Depression severity reduced significantly in both groups, and exercise intervention proved to be just as effective as therapy.

The most interesting study I came across, published in May 2023, compared the effects of antidepressants or running therapy on mental and physical health in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. The study involved 141 participants with depression or anxiety. One group received antidepressants (Lexapro or Zoloft) for 16 weeks. The other group was required to run for 30 minutes two times a week. Remission rates of depression at the end of 16 weeks was 44.8% for antidepressants and 43.3% for running. Both treatments had comparable results for improving mental health. But there’s more . . .

The running group saw improvements in blood pressure, heart rate, waist circumference and weight. And if you feel depressed, reducing your waist circumference and losing some weight will most likely help you feel better. Again, exercise has the ability to improve physical and mental health. There’s more . . .

Antidepressants have side effects. Lexapro can cause diarrhea, dry mouth, heartburn, sleepiness, or trouble sleeping. Zoloft can cause unusual bleeding, bruising, seizure, vison changes, eye pain, headache, confusion, weakness, racing thoughts, and unusual risk-taking behavior. I think I’ll do the running.

But what about strength training? A study published in 2019 found strength training just as effective as aerobic training for treating depression. Combining both yields even better results. Of course, my favorite form of aerobic training is walking outside and sprinting occasionally.

The final study I want to share focuses on brain plasticity—a process that involves adaptive structural and functional changes to the brain. A meta-analysis in 2020 examined the effects of exercise on brain plasticity and depression. Depression can change the physical structure of the brain. Researchers have shown that both aerobic and resistance exercise reshape the brain structure of depressive patients. It appears that exercise can reshape and strengthen neural connections in the brain similar to the way it can strengthen and reshape muscles and peripheral nerves.

Suicide prematurely ends too many lives. While there’s no fool proof way to prevent suicide, I believe exercise can save a lot of lives. But exercise offers just part of the intervention needed to prevent suicide. Pay attention to your friends and loved ones. Stay connected. If someone you know just doesn’t seem like themselves, take the time to ask if they need someone to talk to. If someone really needs help, don’t forget about the 988 Suicide Crisis Lifeline.

Stay Strong,

Bo Railey